When I first started reporting, way back in 2002, historic preservation wasn’t a given, at least in the South. Although cities had moved away from urban renewal, the county commissions I covered prioritized suburban sprawl at all costs. Downtown revitalization was growing, but many developers were still skeptical — after all, it was cheaper to knock something down and quickly build new, shoddy construction than to restore what was already there.

Two decades later, things have changed. Fragile buildings are still falling, especially in rural areas, but historic neighborhoods have become a selling point for chambers of commerce. Housing prices in gentrified historic neighborhoods have skyrocketed, while prices in many suburbs haven’t kept pace. Warehouses-turned-lofts have gone from housing struggling artists to housing finance bros.

There’s an essay to be written about the luxury commodification of historic preservation, and this isn’t it. But the rise — and expense — of historic preservation continues to raise questions about equality, equity and racial and economic justice. After all, how many of those historic neighborhoods didn’t become worth preserving until white people moved in?

I know academics and cultural historians have written about this, and I’m not breaking new ground here. But I keep thinking about the question of who historic preservation is for — likely because I’ve never truly interrogated it.

I grew up in an old house, in a neighborhood of old houses. I lived in old apartments in college — there wasn’t much new, in-town construction in the Northeast at the time. I lived in a literally crumbling Victorian in Athens, then a better-kept up c. 1940s cottage. I’ve lived in a warehouse-turned-loft condo and two mid-century ranches (and two newer ‘80ish homes). I’ve always assumed that were I ever to have the money to buy a house, it wouldn’t be new construction — it’d be old, full of intact period details and drafty windows that need weather stripping. The charm, the appeal, the history!

Of course, having lived in so many old houses, I am fully aware of the drawbacks. The bad plumbing, the creaky floors, the janky wiring, the heating bills in winter. But the perceived virtue of an old home has always won out.

I think it’s only been during the past few years, as ridiculously high rents have prevented me from living on my own, that I’ve begun to question some of my ingrained beliefs about historic preservation. What if some overlays aren’t about keeping neighborhood character but about keeping affordable housing (and poorer people) out? What if some buildings are better off being torn down when what would replace them would serve more people? What if history shouldn’t be preserved at all costs? What if change is inevitable, and we should just embrace it?

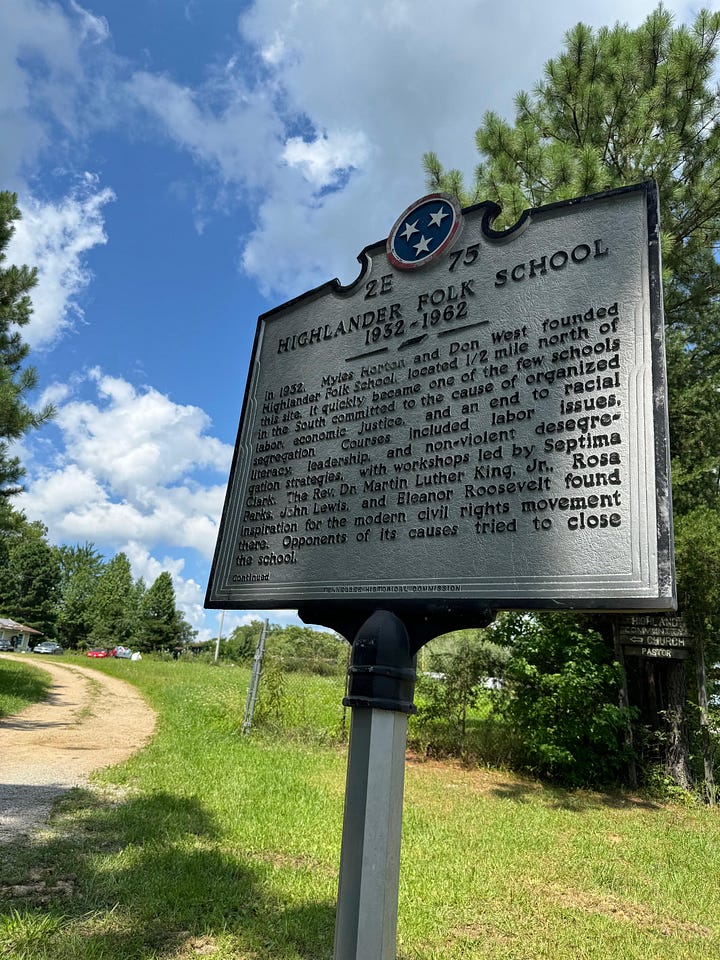

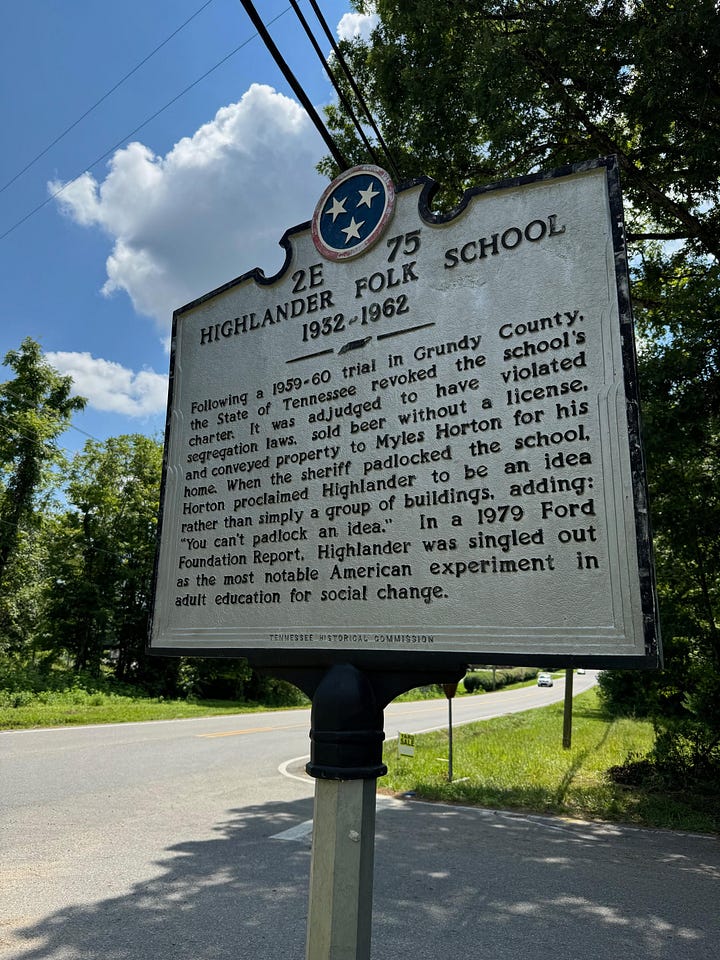

I’ve been thinking about this lately because of a story I just reported1 on the struggle over the ownership of the original Highlander Folk School on Monteagle Mountain. In 1961, the state confiscated the school’s land (famous for training Rosa Parks, John Lewis, Diane Nash and many others). It then moved to East Tennessee and has continued fighting for equality in other ways for the past 60 years. During 2014-19, the nonprofit Tennessee Preservation Trust (TPT) bought some of that original land, including the library building, to preserve it. They’ve now decided to sell the lots to Todd Mayo, the owner of the concert venue The Caverns, even though Highlander has offered $200,000 (in cash) more than Mayo. Highlander staff, understandably, are upset — the land was stolen from them, without compensation, and now it feels like it’s being stolen again, and by people who don’t know the full story.

“Let’s say I was gonna discuss your family history — I probably could study it and maybe talk about it, but I would never be able to do it in the same way that you could as a member of that family, because there are certain things that I wouldn’t be privy to,” said Tennessee State University history professor Learotha Williams, who supports Highlander owning its original land. “Same thing with Highlander. Nobody can tell that story like they can tell it.”

That seems obvious, right? Highlander has the archives, the staff, the budget, the ties to families who were part of the organization years ago. But the only TPT board member who spoke to me, who spoke on background and not for attribution, told me one of the reasons that TPT turned down Highlander’s much more generous offer was because they didn’t want to work with TPT on the interpretation of the site.

“TPT has taken the lead on [the site] for a decade, and we own it,” the board member said. “We bring the knowledge of historic preservation and stewardship to the relationship. And they were just hostile to it the whole time.”

And there lies the crux of the problem. History isn’t told by the winners, it’s told by the owners. Williams says that in one of his classes, he teaches a section about memory and plans to discuss the Highlander situation this fall.

“Who controls memory and how we celebrate things — that’s one of the things I do in my courses,” Williams said. “I talk about historical memory, but I also talk about historical amnesia.”

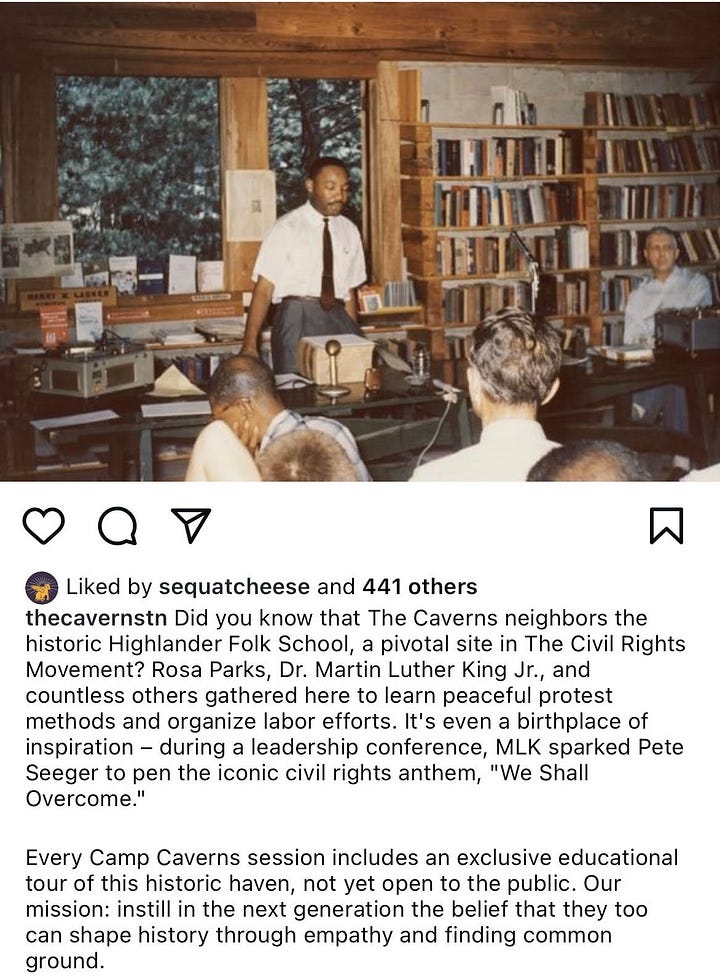

So what is the history the prospective owner wants to tell? Here’s how Mayo explains it:2

I found out through David [Currey, the former TPT board member who led the purchase of the site] that in fifth grade in the Tennessee Core Curriculum and in high school, students learn about Highlander. And so I said, ‘Wow, what if we created a program where we could bring students up there — instead of just reading about it in a book.’ [They could] come up there and learn what happened there and be inspired by the change that happened because people came together to find common ground and to work for solutions for economic justice, racial justice — all these things that are so wonderful …

The pilot program that we’ve done — we have a camp that we do at the Caverns called Camp Caverns, and the last few years we brought the kids up. But I want to get a bus — there are plenty of rural schools in Tennessee and plenty of urban schools and suburban schools that are super underfunded and don’t have the money for field trips — so I want to start bringing kids up there for free on field trips to learn about it. So the goal is to really have every single fifth grader or high schooler in Tennessee make a trip to the historic Highlander Folk School and learn about the history where it took place …

There’s the famous Highlander Lake, and we’ve taken the kids out there during camp and they talk and think about what they can do to make the world a better place. And they have three pebbles and, and we say, ‘Look, this isn’t a wishing well. This is a positive intention. So make an intention — something you can do to make the world better, and throw one rock in and watch those ripples.’ So they throw one rock in alone, and then everybody does it together and looks at all those ripples. And then the last rock they keep. But it’s like, what went on here ripples through time and in positive ways continues to reverberate. So that’s what inspired me to help tell the story.

Mayo seems incredibly sincere (if vague) in his desires and dreams for Highlander. He produced a 2023 PBS series called Ear to the Common Ground, in which a musician and their fans have a potluck and discuss a single political topic to “replace contempt with compassion.” As a longtime political reporter, I am skeptical that such interactions will ever change anyone’s understanding of things. But Mayo seems to deeply believe in “the power that music has to bring people together,” as he told me.

However, as Williams pointed out, the Highlander site isn’t just an inspiring story about the Civil Rights Movement — it’s a complicated and messy one.

“That building represents what is best in America, but this space also represents the worst in America,” Williams said. “Because while Highlander was present down there in Sewanee, that whole idea of equality was something troublesome.”

Any potential Highlander memorial or museum, whether telling a simple story for schoolchildren or a more complicated truth, faces another complication — many people in Grundy County would rather Highlander stay in the past.

One neighbor who lives catty-corner from the site, Michelle Condra, would be happy with all the land returning to residential use.

“I would rather it be torn down and be just land before they do anything with it,” Condra said. “This has been a neighborhood for as long as I can remember … and it’s a real shame that they’re wanting to take places like this back. The history there — it’s just not important to me, if I’m being honest. It’s just history, and it’s served its purpose.”

Her step-brother, Dean Gipson, who lives across the street, said he just hopes they do something with the land.

“I think if you’re going to do something, do something,” Gipson said. “Put a park down here or put a dock on the lake so people can fish.”

The state still owns the lake (which is more of a pond), including a 15-foot easement from the shore, so a dock is unlikely. (Why does the state still own the lake? I don’t know. But it was a massive controversy during the original Highlander days because integrated swimming happened there.)

Another neighbor, a Tracy City cop, said he just wants to stay in the TPT-owned rental house that he’s lived in for ten years. As of now, Mayo isn’t making changes to leases.

“I think it’s probably good to have a police officer living right there on it, you know?” Mayo told me, implying a cop car parked on the corner before you get to the library is possibly likely to deter would-be racist vandals. This may very well be accurate, but there’s an unpleasant irony in a white cop living on land other cops had a big part in taking away from the rightful owners.

If Highlander were to end up with (some of) the original land, they say they’d work with Grundy residents for economic justice, much as the founders did. (Highlander focused on union organizing in the 1930s and ‘40s before turning to civil rights work. )

“The long-term stewardship interests of our original property are absolutely front and center, but also the long-term wellness of the communities and people surrounding our original home and parcels of our original home,” said Highlander co-executive director Rev. Allyn Maxfield-Steele. “We’re in the business of rural economic development and rural organizing that centers the lives and visions of those most impacted by the problems of our economy, environment and social issues. It is front and center for us every day.”

As someone who spent some time up on the plateau for an abandoned reporting project a few years ago, I can tell you that Grundy County is a complicated and conflicted place. There is a lot of history that people love celebrating — Gruetli-Laager, Beersheba Springs — but those sites don’t raise uncomfortable questions about race and ownership. They also don’t raise questions about people who still live nearby or whose kids do — people who fought for the closure or helped make it happen. One person I spoke to said that, years ago, he used to play cards with friends in a Grundy County shop after hours.

“They had a table, had a glass top on it, and it had a bunch of receipts under this glass top,” he told me. “And one of them — I just happened to look down — and it said on the receipt, ‘Padlocks to lock Highlander Folk School,’ signed by Sheriff Elston Clay. That’s where they had bought the padlocks.”

This isn’t precisely what Faulkner meant when writing, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” But it’s not hard to imagine why Grundy officials are (according to the people I talked to) in favor of Mayo running the site. (On its website, the local Chamber currently touts, “Stop by for a visit. Explore a rich history at the Highlander Folk School, hike the famous Fiery Gizzard, or 4-wheel at Coalmont’s OHV Park.” What you can explore, beyond a state historical marker and an empty building, is unclear.) Tourists and schoolchildren are an easier sell than an activist organization fighting the status quo. Entrenched power structures don’t want to change; in Grundy, some of those structures have been entrenched for generations.

However, Grundy County doesn’t own the land. TPT does. And their grudge against Highlander is personal.

“When TPT was working on the National Register nomination, [Highlander staff] called the people of TPT a bunch of white elitists,” Currey told me. “Do you think TPT was gonna just turn the other cheek and say, ‘Oh, well yeah, I guess we are.’ You just ask yourself that personally, how would you feel if you were attacked like that, after you’ve done all of this work? Then you’re like, ‘Hmm, do I really want to work with these people?’”

The Highlander team has similar animosity, but for different reasons.

“We understand that they don’t like our leadership — Phil said in the last article that came out about it that they’d be open to [a sale of the land to Highlander] should there be a change of leadership and a change of attitude,” Maxfield-Steele said. “And we’ve said, well, neither did the segregationists in the ‘50s and ‘60s.”

Or, as Williams put it, “It feels like Tennessee Preservation Trust would be willing to just burn everything to the ground just to teach these uppity folks at Highlander a lesson.”

So who’s the preservation for? Who will it benefit? Can we save historic sites without privileging white privilege? Williams said one problem is that Tennessee needs a new narrative of historic preservation, and its practitioners aren’t quite there yet.

“I don’t think we really know how to do it properly. … We’re trying to preserve something, but we really don’t know how to preserve it, because heretofore it’s been mostly white men and white women who have determined what we’re going to preserve and what we were going to commit to public memory,” Williams said. “So we get Andrew Jackson, a hell of a lot of Civil War stuff, and then one or two monuments for African Americans who were not troublesome — Black folks who were deemed to be good citizens. But that’s it.”

I don’t know what will happen to the Highlander site, and I don’t know if the narrative of historic preservation will change anytime soon, as the people who have the money to preserve things are also the people with structural power. But I do think the narrative of how we report on historic preservation attempts needs to change, and that’s a goal I can strive to achieve.

Reporting Outtakes

I still have so, so many questions left about this deal, despite all my reporting. Some of those questions probably could have been answered by people who didn’t want to talk. Others? Well, the truth is out there, and you’re welcome to keep digging. But if you read my story and wanted more nitty-gritty details and local color, here you go. If you haven’t read my original story, these outtakes probably won’t make much sense, so go read it!

IS TPT selling the land to reorganize or to dissolve?

TPT, which was first incorporated in 1983, did have staff at one time. It’s unclear why and when that changed in the mid-2010s; previous staff members did not respond to requests for comment.

The one board member who spoke on background told me that selling the land was part of a plan to get TPT back on track as a functioning nonprofit.

“Highlander has been like this albatross around our neck, and we’ve got to sort this out before we can go back to our broader mission of doing preservation education across the whole state,” they said.

However, others are under the impression TPT is selling the lots so it will no longer have assets and then can functionally dissolve. But one thing is clear — one of the donors who helped TPT buy the land is calling in their loan. Thomason told me the immediacy of paying that donor back was a big part of the sped-up timeline for the sale.

There are more reasons TPT and Highlander disagree about the sale.

The board member who spoke on background said another reason they voted against the plan was because Highlander wouldn’t commit to placing a preservation easement on the site.

“For us to carry out our mission, that’s part of the deal,” the member said. “That’s just how it works in our field. If you really wanna save something, that’s what you do.”

But Evelyn Lynn, special projects organizer at Highlander, says TPT never mentioned an easement. She says Highlander would have gladly included one in the paperwork if asked.

“TPT has owned the land for a decade and never filed for an easement, so this argument doesn’t hold water,” Lynn says.

Lynn provided a June email from their lawyer to Thomason asking whether TPT was “aware of any agreements, restrictions, easements, or other limitations that will affect the use and maintenance of the properties.” Thomason allegedly did not respond with information either about a preservation easement or the 99-year lease with Kindred.

However, the board member also said timing was an issue — that Highlander was requesting too long a period of due diligence and that would have prevented TPT from a timely payment to the donor calling in his loan. Lynn says that the contract had a due diligence period of a maximum 75 days after signing and it would not necessarily have taken that long.

Currey already has a full-time museum job.

One other question about Kindred — does Currey even have the time to help turn it into a functioning nonprofit that manages a functioning tourist site or museum? In addition to his Encore Interpretive work, Currey is currently the interim executive director of the Coolidge National Medal of Honor Heritage Center in Chattanooga, a position he’s held since October 2021 since being upgraded from his position on the Board of Trustees there. According to the organization’s most recent 990, Currey received $109,680 in compensation in 2022. (Currey still lives in Nashville, though.)

There are even more Kindred questions.

Brian Tibbs was on vacation and couldn’t fill me in about his lack of involvement with Kindred, but I’m not the only person he’s told that he’s never been on the board. Currey told me that a history professor at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, Tara White, has also joined the Kindred board for 2024. White initially said she would comment on this story but then declined to reply to further calls and texts, so her involvement remains unclear.

The biggest issue with a lack of board members? A potential lack of accountability for donations. Mayo says he donated money to help restore the library; the library clearly did get restored. Currey told me that beyond the library, funds were spent on videos.

“We did some interviews with John Lewis and Andrew Young, but other than that, that’s all Kindred was ever used for,” Currey said.

However, when I interviewed Ted Debro, he said Currey filmed videos of Young and Lewis, along with victim Sarah Collins Rudolph, for the 16th Street Baptist Church exhibit. Did Currey film extra videos on his own time?

No one has accused Currey of any financial malpractice, and he claims to have spent a lot of money out of his own pockets to keep up the Highlander site.

“I still pay for mowing the grass up there. I’ve been paying for it for, you know, almost a decade,” Currey says. “I pay for the electricity — I personally pay for that. There’s no financial gain there.”

Currey wrote a master’s thesis about that controversial statue in Franklin.

A few years ago, there was a big fight over possibly removing “Chip,” the Confederate soldier statue in downtown Franklin. (Because Tennessee law makes such removals nigh impossible, the town added a Black soldier statue next to him.) Well, Currey wrote his 1996 master’s thesis at MTSU about that statue and how the United Daughter of the Confederacy preserved and promoted Lost Cause mythology in Franklin after the Civil War. Multiple people raised questions about the thesis and whether someone who chose that topic should be the person running the Highlander site.

While not exactly pro-Confederate, the thesis does lack much mention of the racial terrors also promulgated by Lost Cause myths. However, Currey now says that he wouldn’t have written anything differently, even with the passage of time.

“Are [the UDC] peddling all this other stuff [like lynching] too? Of course they are. But we’re trying to come to an understanding of why they thought that way,” Currey says. “There’s a difference between interpretation as an individual on a personal level, and as a historian. So the notion that what I’m writing in some way or another makes me a racist when all I’m doing is interpreting how those people believe themselves — that’s people who don’t understand a history book.”

For the record, no one that I spoke to called Currey “racist.” I’ll leave it to the historians out there to determine if Currey’s thesis holds water.

You don’t have to read the piece, but I’d recommend it — it’s good, and will provide better context.

I have condensed some of the transcription for space and clarity but have not changed anything significant.

Excellent reporting and insight, as always. Sure seems like someone isn't doing what's right/best/most financially beneficial because his feelings got hurt. I would like to think all of the conflict of interest murkiness would be enough to cause the AG's office to intervene, but I also know better in this state. The whole thing stinks.